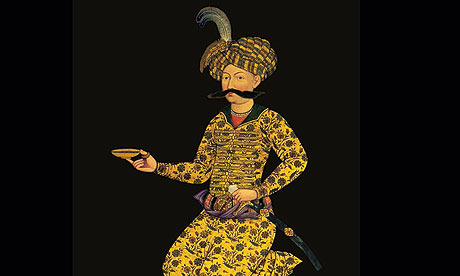

A detail from the wall of Chihil Sutan Palace in Isfahan showing Shah Abbas. Photograph: British Museum

Madeleine Bunting visited the magnificent city of Isfahan ahead of an exhibition celebrating the Persian ruler Shah Abbas I, who aimed to put his nation at the centre of the world. Thirty years after the Iranian revolution, she finds the past can deepen our understanding of a country that provokes both fascination and fear

Stand on the roof terrace of the Ali Qapu palace overlooking the central square of Isfahan, Iran's most beautiful city, and you begin to grasp the significance of Shah Abbas I (1587-1629), arguably the country's most brilliant ruler. Before you lies the masterpiece of urban planning that integrated the political, economic, religious and social elements out of which he built a nation. Here is an architecture which perfectly expresses the political economy of its ruler and enabled him to claim that his country was at the centre of the world.

- Shah Abbas: The Remaking of Iran - British Museum, London , WC1 , Starts 19/02/2009 - Until 14/06/2009 - Details: 020 7323 8181 - Visit the British Museum's website

- Note : عباس: از عبس ميآيد به معناي اخمو، ترشرو، ترسناك و بدخود

The square, Naqsh-i Jahan, is one of the biggest urban spaces in the world; at 500 by 160 metres, its scale is surpassed only by Tiananmen in Beijing. Opposite the palace are the exquisite minaret and dome of the Shah's private mosque, the blue tiles gleaming in the late afternoon sun. As the muezzin sounds, Isfahani families begin to lay out rugs among the fountains and garden of the square. The moon is rising and it catches the imposing public mosque - the Masjid-i Shah - which dominates another side of the square. The fourth side is taken up by the entrance to the bazaar, still one of the biggest in Iran. It was on the Ali Qapu terrace that the Shah entertained ambassadors from China, India and Europe with military parades and mock battles. This was the stage he used to impress the world; his visitors, we are told, came away stunned at the sophistication and opulence of this meeting point between east and west.

Shah Abbas: The Remaking of Iran, a major exhibition at the British Museum, is the third in a series on rulers who have changed the world (the fourth will be on the Mexican ruler Montezuma). Previous subjects have been familiar - the first emperor of China and the Roman emperor Hadrian - but this latest show takes the visitor into what for many will be new territory: a country much misunderstood in the west and a little-known period in its long history. Abbas's story sheds fascinating light on how nations acquire power and how they sustain it. "The British are very naive about the acquisition - and loss - of power; we have a sort of amnesia about how we lost our empire," says Neil MacGregor, the museum's director. "We grew up with the stability of American and Soviet empires and we are now seeing the rise of China, Russia and India. Our ignorance of other empires was part of our political project of supremacy, but it is now crippling our capacity to manage our relations with the countries over which we once established that supremacy. Iran has never been able to be naive about power, given its geostrategic significance in central and western Asia. Under Abbas, it became adept at using soft power."If you want to understand modern Iran, arguably the best place to start is with the reign of Abbas I, and nowhere better demonstrates his ambition than Isfahan, his new capital. Abbas had an unprepossessing start: at 16, he inherited a kingdom riven by war, which had been invaded by the Ottomans in the west and the Uzbeks in the east, and was threatened by expanding European powers such as Portugal along the Gulf coast. Much like Elizabeth I in England, he faced the challenges of a fractured nation and multiple foreign enemies, and pursued comparable strategies: both rulers were pivotal in the forging of a new sense of identity. Isfahan was the showcase for Abbas's vision of his nation and the role it was to play in the world. In the Shah's palace of Ali Qapu, the wall paintings in his reception rooms illustrate a significant chapter in the history of globalisation. In one room, there is a small painting of a woman with a child, clearly a copy of an Italian image of the Virgin; on the opposite wall, there is a Chinese painting. These pictures indicate Iran's capacity to absorb influences, and demonstrate a cosmopolitan sophistication. Iran had become the crux of a new and rapidly growing world economy as links were forged trading china, textiles and ideas across Asia and Europe. Abbas took into his service the English brothers Robert and Anthony Sherley as part of his attempts to build alliances with Europe against their common enemy, the Ottomans. He played European rivals off against each other to secure his interests, allying himself with the English East India Company to expel the Portuguese from the island of Hormuz in the Persian Gulf.The bazaar at Isfahan has changed little since it was built by Abbas. The narrow lanes are bordered with stalls laden with the carpets, painted miniatures, textiles and the nougat sweets, pistachios and spices for which Isfahan is famous. This was the commerce that the Shah did much to encourage. He had a particularly keen interest in trade with Europe, then awash with silver from the Americas, which he needed if he was to acquire the modern weaponry to defeat the Ottomans. He set aside one neighbourhood for the Armenian silk traders he had forced to relocate from the border with Turkey, aware that they brought with them lucrative relationships that reached to Venice and beyond. So keen was he to accommodate the Armenians that he even allowed them to build their own Christian cathedral. In stark contrast to the disciplined aesthetic of the mosques, the cathedral's walls are rich with gory martyrdoms and saints. It was the need to nurture new relationships, and a new urban conviviality, that led to the creation of the huge Naqsh-i Jahan square at the heart of Isfahan. Religious, political and economic power framed the civic space in which people could meet and mingle. A similar impulse led to the building of Covent Garden in London in the same period.There are very few contemporary images of the Shah because of the Islamic injunction against images of the human form. Instead he conveyed his authority through an aesthetic that became characteristic of his reign: loose, flamboyant, arabesque patterns can be traced from textiles and carpets to tiles and manuscripts. In the two major mosques of Isfahan that Abbas built, every surface is covered with tiles featuring calligraphy, flowers and twisting tendrils, creating a haze of blue and white with yellow. The light pours through apertures between arches offering deep shade; the cool air circulates around the corridors. At the centre point of the great dome of the Masjid-i Shah, a whisper can be heard from every corner - such is the exact calculation of the acoustics required. Abbas understood the role of the visual arts as a tool of power; he understood how Iran could exert lasting influence from Istanbul to Delhi with an "empire of the mind", as the historian Michael Axworthy has described it.Central to Abbas's nation-building was his definition of Iran as Shia. It may have been his grandfather who first declared Shia Islam as the country's official religion, but it was Abbas who is credited with forging the link between nation and faith that has proved such an enduring resource for subsequent regimes in Iran (as Protestantism played a pivotal role in the shaping of national identity in Elizabethan England). Shia Islam provided a clear boundary with the Sunni Ottoman empire to the west - Abbas's greatest enemy - where there was no natural boundary of rivers or mountain or ethnic divide.The Shah's patronage of the Shia shrines was part of a strategy of unification; he donated gifts and money for construction to Ardabil in western Iran, Isfahan and Qom in central Iran, and Mashad in the far east. The British Museum has organised its exhibition around these four major shrines, focusing on their architecture and artefacts. While Isfahan still seduces every foreign visitor as it was intended to do, it is at Mashad, close to the border with Afghanistan, that the connections between Abbas and contemporary Iran become most clear. Abbas once walked barefoot from Isfahan to the shrine of Imam Reza in Mashad, a distance of several hundred kilometres. It was a powerful way to enhance the prestige of the shrine as a place of Shia pilgrimage, a pressing priority because the Ottomans controlled the most important Shia pilgrimage sites at Najaf and Kerbala in what is now Iraq. Abbas needed to consolidate his nation by building up the shrines of his own lands.Today Mashad is one of the biggest pilgrimage sites in the world, with 20 million visitors every year. In peak season, hundreds of buses arrive each day, and there are 24 daily flights from Tehran alone; passengers at the airport are greeted with a huge slogan above the arrivals gate, in Iranian and English: "Welcome pilgrim to pray to Imam Reza as an intercessor before God."

Hear Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis of the British Museum, at the shrine of Imam Reza Link to this audioTo cope with the volume of pilgrims, huge motorways and underground car parks have been built around the shrine complex. More are planned as this small city of seminaries, libraries, museums and conference centres continues to grow; cranes jostle alongside the minarets. It is also a major business centre - the shrine owns factories, hospitals and agricultural enterprises. Since the Islamic revolution in 1979, money has been poured into the expansion of the shrine much as it was by Abbas in a bid to build legitimacy for his rule more than 400 years ago.Mashad's precincts teem with people from every social background, from large peasant families of several generations to the stylish young Tehrani couples who come here on honeymoon. All the women must be in full black chador, and attendants with bright pink and yellow feather dusters are everywhere to ensure that even the smallest lock of hair is hidden. Every pilgrim wants to touch the shrine of Imam Reza; such is the crush around the golden grille that often it is only possible to get close to it late in the evening or at night. The shrine's vast museum is subjected to the same veneration. The pilgrims touch the doorjamb of the entrance and brush their lips in prayer; many exhibits prompt more touching and praying - donations are left at some. This is a museum unlike any other in the world: a place of worship. The museum's collections are made up entirely of gifts, and the abundance is bewildering: there's a model of Mashad airport, and then the medals of the great Iranian wrestler of the 20th century, Gholamreza Takhti. There is even a lifesize lobster in gold donated by the Supreme Ayatollah. And interspersed among four centuries' worth of giving are the gifts of Abbas, including some beautiful early Qur'ans.Abbas donated his collection of more than 1,000 Chinese porcelains to the shrine at Ardabil, and a wooden display case was specially built to show them to the pilgrims. He recognised how his gifts and their display could be used as propaganda, demonstrating at the same time his piety and his wealth. It is the donations to the shrines that have inspired the choice of many of the pieces in the British Museum show. This is a timely exhibition: a bold attempt to deepen understanding of a country with which our own is locked in a hostile diplomatic impasse. It is only four years since the museum mounted the Forgotten Empire exhibition on Iran's ancient history; it is as if the museum is conducting its own independent foreign policy, using culture as a form of exchange between countries for which other methods of communication are difficult.That is no small order. Iran has provoked fascination and fear in western Europe for more than two millennia. Europeans' knowledge of the country was for a long time second-hand, heavily influenced by the hostility of the historians of ancient Greece. Generations of European elites educated in the classics viewed it through the writings of Herodotus and his accounts of the wars with Persia. Sunni Arab commentators were similarly hostile. The fearful incomprehension has only intensified since 1979. Shia rituals of self-flagellation, intercession, pilgrimage, relics and martyrs can alienate in a Europe that is rapidly forgetting its own version of such rituals in the Catholic tradition. In a world in which most cultures are being brought into closer communication, Iran has arguably become more alien rather than less. That makes the challenge of understanding a critical period in this nation's history daunting - but all the more pressing.

Sir Robert Shirley (c. 1581 – July 13, 1628) was an English traveller and adventurer, younger brother of Sir Anthony Shirley and of the adventurer Sir Thomas.

He went with his brother Anthony to Persia in 1598. Anthony was in Safavid Persia from December 1, 1599 to May 1600. He was given 5,000 horses to train the Persian army according to the rules and customs of the English militia. He was also commanded to reform and retrain the artillery. When he left Persia, he left his brother, Robert, behind with fourteen Englishmen who lived in Persia for years. Having married Teresia, a Circassian lady, he stayed in Persia until 1608 when Shah Abbas sent him on a diplomatic errand to James I and to other European princes. He was employed, as his brother had been, as ambassador to several princes of Christendom, for the purpose of uniting them in a confederacy against the Ottoman Empire.

He went first to Poland, where he was entertained by Sigismund III Vasa. In June of that year he was in Germany, and received from the Emperor Rudolph II the title of Earl (count palatine) and knight of the Roman Empire. Pope Paul V also conferred upon him the title of Earl. From Germany Sir Robert went to Florence and from thence to Rome, where he entered, attended by a suite of eighteen persons, on Sunday, 27 September 1609. He next visited Milan, and then proceeded to Genoa, whence he embarked to Spain, arriving in Barcelona in December 1609. He sent for his Persian wife and they remained in Spain, principally at Madrid, until the summer of 1611. In 1613 he returned to Persia, but in 1615 he came back to Europe and lived for some years in Madrid. In a pleasingly serendipitous meeting Shirley's caravan came across that of Thomas Coryate, the eccentric traveller and travel writer (and attendant of Prince Henry's court in London) in the Persian desert in 1615. Shirley's third journey to Persia was undertaken in 1627, but soon after reaching the country he died at Qazvin. There are several double portraits of Shirley and his wife in English collections, including the private collection of R.J.Berkeley and of Petworth House.

Sir Anthony Shirley (or Sherley) (1565 - 1635) was an English traveller.

He was the second son of Sir Thomas Shirley (1542-1612), of Wiston, Sussex, who was a member of parliament during the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I and who was heavily in debt when he died in October 1612. Anthony's brothers, Robert Shirley and Thomas Shirley, were also much-travelled.Shirley's imprisonment in 1603 was an important event because it caused the British House of Commons to assert one of its privileges--freedom of its members from arrest. Educated at the University of Oxford, Anthony Shirley gained some military experience with the English troops in the Netherlands "and also during an expedition to Normandy in 1591 under Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, who was related to his wife, Frances Vernon; about this time he was knighted by Henry of Navarre (Henry IV of France), an event which brought upon him the displeasure of his own sovereign and a short imprisonment. In 1596, he conducted a predatory expedition along the western coast of Africa and then across to Central America, but owing to a mutiny he returned to London with a single ship in 1597. In 1598, he led a few English volunteers to Italy to take part in a dispute over the possession of Ferrara; this, however, had been accommodated when he reached Venice,

and he decided to journey to Persia with the twofold object of promoting trade between England and Persia and of stirring up the Persians against the Turks. He obtained money at Constantinople and at Aleppo, and was very well received by the Shah, Abbas the Great, who made him a Mirza, or prince, and granted certain trading and other rights to all Christian merchants.

Then, as the Shah's representative, he returned to Europe and visited Moscow, Prague, Rome, and other cities, but the English government would not allow him to return to his own country. For some time he was in prison in Venice, and in 1605, he went to Prague and was sent by Rudolph II, Holy Roman Emperor on a mission to Morocco; afterwards he went to Lisbon and to Madrid, where he was welcomed very warmly. The King of Spain appointed him the admiral of a fleet which was to serve in the Levant, but the only result of his extensive preparations was an unsuccessful expedition against the island of Mitylene. After this he was deprived of his command. Shirley, who was a count of the Holy Roman Empire, died at Madrid some time after 1635. Shirley wrote an account of his adventures, Sir Anthony Sherley: his Relation of his Travels into Persia (1613), the original manuscript of which is in the Bodleian Library at Oxford. There are in existence five or more accounts of Shirley's adventures in Persia, and the account of his expedition in 1596 is published in Richard Hakluyt's Voyages and Discoveries (1809-1812). See also The Three Brothers; Travels and Adventures of Sir Anthony, Sir Robert and Sir Thomas Sherley in Persia, Russia, Turkey and Spain (London, 1825); EP Shirley, The Sherley Brothers (1848), and the same writer's Stemmata Shirleiana (1841, again 1873).

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for your comment. This comment will be posted after it has been modarated by the editor.